Ethnological research as a source of data for planning a sustainable development strategy for rural areas (written by Grga Franges)

Public institution "Učka Nature Park"

Case study: Žumberak

This paper examines the developmental role of ethnology as a science and proposes a method by which the data obtained through ethnological research could be used for the purpose of creating a strategy for the development of a rural area. The case of the Žumberak region, which has experienced accelerated rural decline in the last century due to historical, geographical and socioeconomic reasons, was used as an example to illustrate the above ideas. Having adapted the SWOT analysis method, taken from economics, the author uses it to create a snapshot of the current social situation in Žumberak and the wider circumstances that affect it, and the results obtained with the help of the proposed SWOT relational diagram method are used to synthesize an exemplary strategy for the sustainable development of the Žumberak region.

Keywords: Žumberak, rural decline, sustainable development, SWOT analysis, rural tourism, traditional production

Ethnology is a science that is rarely asked to contribute to the development of society. There is even a widespread view that the development and preservation of traditional culture, which ethnology most often deals with, are two opposing tendencies. This is partly the result of attitudes, sometimes promoted by the profession itself, that treat traditional culture as a set of characteristics frozen at a single point in time, and the only contribution to development is found in its use in tourism as part of the souvenir offer. Every culture is a living process that, in order to survive, must be respected for its right to develop. And looking at broader social development from an ethnological and

from an anthropological perspective, I am convinced that its sustainability requires a foundation in the form of a healthy and authentic culture and identity.

This is especially true when we talk about marginal areas susceptible to rural decline. In their development issues, we are dealing with very complex interrelationships that work on the principles of feedback. The withering away of an area can be conditioned by various changing circumstances: economic, ecological and cultural. However, the end result of all these influences is the breakdown of the traditional value system on which the functioning of the community was based. In order to reverse negative trends, it is crucial to reexamine this value system and help it adapt to the new circumstances – to help the local population regain a sense of meaning and perspective for their lives and work.

I believe that this largely belongs to the domain of our science and that it is the task of ethnologists to point out this perspective of developmental issues and find means that would help resolve them. This paper is a small study on this.

To illustrate these ideas, I chose Žumberak both because of my personal knowledge of the area and because I believe that, of all the areas in Croatia, Žumberak is in a position to benefit from their application.

I. Žumberak – historical background

Even a cursory visit to Žumberak will show you that it is a very attractive area for human habitation. The relief, crisscrossed by numerous watercourses inhabited by fish and crustaceans, rises into wooded hills that are sheltered by gentle slopes of lush pastures or valleys with quality agricultural land. The mountain climate, with cold but not too long winters, mild summers and abundant rainfall, is conducive to the growth of pastures full of essential herbs and flowers, which is particularly suitable for livestock and beekeeping, and the southern slopes of the hills make good orchards and vineyards.

The first human settlers to this area did not find it as we see it today. Thirty percent of the current territory of Žumberak, as a result of human cultivation, is covered with meadows and agricultural clearings, while in its original state it was covered with forest. Over thousands of years, a stable ecosystem has been established around them, in which the local human population, through clearing, prevented the return of the forest, thereby creating a living niche for numerous plant and animal species. To this biological wealth of Žumberak we must also add the geological one: dolomite and other limestone rocks that the local soil abounds in have proven to be a source of high-quality building material, and the presence of copper and iron ore contributed to the fact that the inhabitants of these regions were among the first in this area to master the skills of metalworking.

Throughout history, various peoples have lived in Žumberak: Celts, Illyrian tribes, Roman settlers and, finally, Slavs. After the depopulation of this region, which

due to frequent Turkish incursions began to take place five hundred years ago, the imperial authorities decided to solve the problem of population shortage by directing refugees from the areas occupied by the Turks here. This last wave of migration to Žumberak laid the foundations of today's population and its local culture. They were the livestock-breeding population of the Dinaric region, accustomed to a similar natural environment. They brought with them characteristic building methods, techniques for processing and decorating textiles, and many other economic and cultural features. As an area of the Military Border, Žumberak was primarily intended by the imperial administration for a defensive function and was bypassed by investment in the education of the population and the modernization of economic practices, characteristic of the Age of Enlightenment in the rest of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Thus, with the abolition of the Military Border and military revenues in the second half of the 19th century, the Žumberak region found itself in the position of an economically backward area.1 2

In the period after World War II, when the peasantry was further impoverished by war events, we witnessed a massive depopulation of the Žumberak area. As the younger generation migrated, the reproductive potential of the local population declined. There were fewer children and local schools were closed, which, creating a kind of vicious circle, gave the younger population an even stronger motive to emigrate.

Žumberak is today sparsely populated by an elderly population that is no longer able to adequately utilize and care for agricultural and pasture land. Due to this lack of agricultural and livestock activity, meadows and pastures are overgrown with undergrowth and hornbeam. Today, not only the human community is dying in Žumberak, but also the characteristic landscape that depended on symbiosis with people.

II. Analysis of the current situation

I have tried to build a picture of the current situation, problems and prospects of Žumberak from several sources: personal field observations, facts collected from literature, documentation and conversations with employees of the Public Institution "Žumberak and Samoborsko gorje Nature Park". The most significant source is a series of structured interviews with local residents collected during a ten-day field research in May 2005.

Ethnology does not have any analytical methods in its arsenal that are directly intended for active reflection on development strategies. Therefore, I borrowed and used the SWOT analysis method from the world of business management for this research. SWOT is an acronym for the English words: strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats. This method is used to evaluate the current situation in strategic planning. After we set the ultimate goal that we want to achieve, in our 1 2

1 Štambuk, M. (1996) Introduction; 7-9

2 T. Šola, 2001; 229

In the case of the sustainable development of the Žumberak area, we divide the factors that influence the achievement of that goal according to their origin (internal and external) and according to the impact they have on that achievement (helping or hindering).

Since the acronym SWOT does not essentially oblige me to present these categories in the order they are presented, I decided, in accordance with the Žumberak situation, to start with the negative.

II.l. Weaknesses

OR.a) Small and aging population

According to the last census conducted in 2001, the area of the Žumberak municipality was inhabited by 1,185 inhabitants, of whom 533 were over sixty years of age.3 If the tendency of extinction were to continue at the current pace, this municipality would remain almost completely uninhabited for several decades.

In conversations with the local population, the painful human dimension of these figures is revealed. An old man from Kekić, who, like a kind of guardian, is the last real resident of the village, says of his existence: “It’s sad here. I didn’t get married, so I’m the only one left. My mail is in Canada, and the rest is scattered everywhere. Sometimes they send me dollars, but even that is rare. […] When I get a few dinars; I usually go four kilometers to Sošice for a drink just to talk to someone.”

If I came across a younger interlocutor, the direct reason for his stay in the village would often be revealed immediately after the meeting: deaf-muteness, physical deformity, alcoholism, and the like.

As silent witnesses to this demographic collapse, beautiful peasant houses stand ghostly abandoned, and meadows and fields overgrown with undergrowth.

II.lb) Collapse of the community - defeatist attitude and disunity

"And why would anyone come back? You too, run away while you can!"

The old man from Cernik

Probably the most difficult task in my conversations with the people of Žumberak was trying to get some idea from them about Žumberak's advantages and opportunities. Most of my interlocutors, taught by their previous experience, were extremely skeptical about any possibility of recovery.

This low assessment of one's own possibilities and prospects is a key factor in the collapse of the Žum-Beračka people. Part of the problem certainly lies in the breakdown of the traditional value system. The peasants here have never been rich, but it used to be difficult to feed and house one's family.

http://www.dzs.hr/Hrv/Popis%202001/popis20001.htm

own work was a sufficient and socially valued economic aspiration. Other life needs, such as entertainment and spirituality, local community and culture, were also satisfied within their own frameworks. However, the time came when the economic yardstick became money, entertainment what was shown on television, and cultural creativity something that, according to the dominant view today, the peasants had no idea about. According to Mr. Marijan, the owner of a shop in Kalj: “We were poor, but life was still beautiful. The way we socialized and helped each other… Everything went to hell when people started coming back from Germany with cars, with televisions… Suddenly this old stuff was no longer good for anyone.”

A culture that once provided a framework for a difficult but fulfilling life has suddenly become backward, without prospects, and doomed to a slow withering away – many of its current heirs, like the aforementioned gentleman from Cernik, would rather spare it the agony. All of this has led to the prevailing attitude of “every man for himself” – with the decline of the old sense of community, people have largely given themselves over to a life in which they try to make ends meet in their own difficult existence and do not see how they can help each other or act together to defend their interests.

II.lc) Lack of education and bad culture of living and production

When visiting households in Žumberak that are still economically active, the conversation often turns to the prospects of local dairy farming or rural tourism and various other opportunities for additional income. However, I have often found myself in the uncomfortable situation of seeing a huge obstacle to the realization of such plans during the conversation, and that I cannot tactfully remind my interlocutors at that moment. It is a problem of hygiene – how can you help someone market their cheese without ever washing their cow's udders and without asking themselves about their own responsibility for possible consequences? How can you send guests to a household where basic hygiene measures are not practiced? Far from it, this situation is the norm for Žumberak. Most of the houses I have visited were distinguished by an enviable level of tidiness, but still, this phenomenon is too frequent in my observation to be treated as a problem.

There are, of course, reasons for this situation, and in resolving it, a great deal of understanding should be shown for the circumstances these people find themselves in – who ever tried to provide them with a better ideal of living and working habits and give them reasons and means to accept it?

Il.ld) The terrain makes transport connections and infrastructure construction difficult

To experience this problem, which is often highlighted by local residents, it is enough to get in a car and drive from Zagreb to Budinjak. The first thirty kilometers of the journey from Zagreb to Bregana will take about fifteen minutes on a modern highway. The next thirty kilometers of winding mountain roads to Budinjak will take about an hour. If you try to reproduce this journey using public transport, you will see that it is a completely impractical undertaking for everyday conditions. While some areas further from Zagreb can count on the advantages of being close to the capital, in Žumberak this is now another reason to move away.

IL Le) Inadequacy of the region for the development of modern industry

Due to its specific relief, lack of transport connections and demographic weakness, Žumberak is not an area that attracts typical investments. Most of today's industrial branches will perform their production and service activities much more simply and efficiently in areas with better transport connections and a larger pool of young and educated labor force. The same applies to modern industrialized agriculture, which, despite all this, can hardly gather large enough land plots for efficient production in Žumberak.

While these facts are mostly seen as a weakness and another factor in pessimistic predictions of Žumberak's future, it is more constructive to view them as a local specificity that requires different development approaches. Ultimately, it is precisely the lack of modern industry that has contributed to Žumberak remaining an ecologically and culturally unpolluted area.

Il.lf) Land parcelization and undefined ownership

"And you would like to buy that? And from whom? Half of them went to Canada, and the other half I don't know."

where·"

An old man from Cernik in response to my casual interest in a beautiful country house

The problem of too small land plots is of such proportions that it calls into question the normal existence of the village. The division of land for inheritance has led to the fact that most of the people of Žumberak own several small and scattered plots.4 which is very difficult to adequately utilize. And even if someone wanted to buy or exchange land, in order to increase their agricultural production, the problem of unresolved ownership relations often arises.

This problem is also a major obstacle to starting rural tourism. Many old village centers require minimal investment to be transformed into first-class tourist attractions, for which there is even a willingness among local residents. However, an element of uncertainty is introduced into these ideas by the fact that potential claimants of ownership rights to individual objects are scattered around the world, from Zagreb, through Germany, to Canada and Australia.

II.lg) Administrative disunity

In 1995, Žumberak was divided into three administrative areas – the City of Samobor, the Municipality of Žumberak and the City of Ozalj. Given that this is undoubtedly a culturally and geographically integral area that requires a comprehensive development approach, this is not the most fortunate solution. The residents of Gornja Vas and Novo Selo Petričko live similar lives, carry out their activities on the same land, and even buy supplies in the same store. However, they are separated by an administrative border, and some have to solve their problems in Samobor, and others in Sošice, with their own sets of local authorities that do not have many formal channels of mutual communication.

There is also the issue of the state (and currently the Schengen) border that separates Žumberak from the Slovenian Gorjanci, which are also a geographically, culturally and touristically similar area.

4 Magdalenić, I., Župančić, M. (1996)

Stoj Draga and Kamence are neighboring villages, each on its own side of the border, connected by a five-hundred-meter-long macadam road, and traditionally enjoyed good neighborly relations and economic cooperation. However, if they wanted to visit their neighbors legally today, the people of Stoj Draga would have to make a circuitous route of about eighty kilometers through the nearest official border crossing.

Π.2. Advantages

II.2.a) Attractive and preserved natural landscape

When someone is taken to Žumberak for the first time, they usually cannot help but be amazed that only forty kilometers from Zagreb there is such an untouched landscape where you can drink water from a stream, swim under a waterfall, walk for hours without encountering any sign of civilization, and encounter wild boars, deer, falcons and even bears. The natural heritage of Žumberak constitutes an enormous ecological and social capital, both for this area and for the whole of Croatia, which is waiting to be adequately and sensibly used.

II.2.b) Enthusiasm of individuals and pride of local residents in their area

"We came back here against all those who were leaving. They thought we were crazy, and laughed at us behind our backs."

Mr. Subie from Stojdraga

In contrast to the prevailing defeatism, in Žumberak, although rarely, you can come across individuals who express immense faith in the bright future of this region. Among the people I met during my travels around Žumberak, this quality is well embodied by the Subie family from Stojdraga. Having educated their children in Bregana, they decided to return to Stojdraga, where Mrs. Subie comes from, and start a business. The future of such a beautiful region, rich in cultural and natural heritage, which is also so close to the capital, is guaranteed in their eyes – it is only a matter of time before this potential is recognized and their ideas gain meaning.

Such sentiments about Žumberak are also hidden in many individuals who are at first glance complete defeatists. It is only necessary to dig a little deeper beneath that pessimistic surface, present a few possible ideas, encourage them to think about the riches and possibilities of Žumberak for themselves, and you will encounter hope and love for your region. Although in the end, many, having learned from their previous disappointing experience, will still summarize such a conversation as, for example, Mr. Marijan, the owner of a shop in Kalju: “I hope so much that what you are saying is possible, but I am afraid that you have come too late.”

Such sentiments of local residents, so much love and enthusiasm, are an exceptional creative energy that needs to be channeled before it really becomes too late.

11.2. c) Specific local culture with an unusual history

The history of human settlement in Žumberak is multi-layered and dramatic, as evidenced by numerous archaeological monuments. Today's inhabitants of Žumberak, as heirs of this history, have preserved their specific features that set them apart from the surrounding area - their Greek-Catholic religious affiliation and an interesting mix of Dinaric and pre-Alpine cultural features and economic practices. This unique and endemic local culture can serve as an excellent foundation for building a specific Žumberak tourist identity and inspiration for entrepreneurial ventures and sustainable development of the region.

11.2. d) Preservation of the region for traditional and ecological production and rural tourism

The developmental neglect of Žumberak has had one somewhat positive effect – it has insulated it from the spontaneous change in lifestyle and modern economic practices, the sustainability of which could potentially prove to be very questionable. There are no collapsed mastodon industrial plants from the era of socialist progress in Žumberak. The fields and waterways of Žumberak are not soaked with insecticides and artificial fertilizers, which provides the basic prerequisite for starting organic agriculture. The old houses, mills and gazebos in Žumberak are dilapidated, but at least every trace of them has not been erased, as was the case elsewhere.

11.2. e) Unifying initiatives and institutions

Despite the administrative disunity of Žumberak, in many aspects it was impossible to ignore the obvious uniqueness of this area. Thus, on 28 May 1999, for the purpose of protecting the natural heritage of Žumberak and the Samobor Mountains, the Public Institution "Žumberak Nature Park - Samobor Mountains" was proclaimed by law. The Nature Park is not a local government body and outside of its primary activity, which is the protection of the Žumberak landscape, it does not have specific authority and powers, but it can serve as a coordinating institution for initiating sustainable development projects that would encompass the entire Žumberak area. This institution already plays a key role in creating tourist and recreational infrastructure by marking and maintaining hiking and cycling trails, marking places of heritage importance, printing tourist maps, opening information centers, exhibition spaces and souvenir shops in its branches, and numerous other activities. The Nature Park is also a potential main channel for presenting Žumberak to the world - through media promotion of the area, organizing public recreational and cultural activities, and promoting local products and services.

Another initiative worth mentioning is the establishment of the Tourist Zone along the Kupa and Žumberak (Gorjanci) and the Tourist Zone along the Sutla and Žumberak (Gorjanci).5 The goal of this initiative, which was launched by the Croatian Chamber of Commerce in Zagreb, the Chamber of Commerce of Slovenia and local mountaineering associations, is to connect Žumberka on the Croatian side and Gorjanci on the Slovenian side of the border. As part of this initiative, joint efforts would be made to enrich and promote the tourist content of this region, and visitors and residents would be able to cross the state border without hindrance. This can be done

5 http://www.smallisbeautiful.org/publications/essay_currency.html

can also be considered as a type of preparation of local tourism for the expected liberalization of the border regime brought about by Croatia's entry into the European Union.

Π.3. Threats

11.3. a) Culture of mass production and consumption

The development of consumer society in Croatia started relatively late but is showing astonishingly rapid progress. Many forms of traditional economy are still alive and well in Croatia, as we will see if we visit any of the city markets and (today with some searching) buy vegetables, honey, dairy products and the like directly from farmers. However, this sector is receiving new blows every day from the onslaught of industrial products and their aggressive marketing or simply lower prices. More and more consumers, out of pure convenience, today prefer to buy products traditionally supplied at the market in some shopping mall, and even the market itself is now dominated by overbuyers.

Croatian society today is at a crossroads where it is choosing whether to reject these traditional forms of economy once and for all or, like some other European countries, to embrace them as a unique cultural, health and ecological value. This issue is of exceptional importance for the future fate of Žumberak. Such a radical change in our consumer habits is in fact a complete change in our culture of living, and if such a trend continues to its hypothetical extreme, the considerations about the future of Žumberak that I am dealing with in this paper will truly be completely pointless.

11.3. b) Pollution of the environment and culture through uncontrolled tourism

It's nice to see how the once "self-governing" ideal of a family vacation in nature, with a car, a crate of beer, and grilled meat, coexists beautifully with the achievements of a consumer society. After all, there are more cars than ever to park in green meadows, as well as more plastic packaging and other trash to scatter in nearby bushes.

The natural environment is not the only thing at risk from uncontrolled and reckless tourism. As we can see from the example of our coast, the concreting of once beautiful rural settlements and the crowding out of local culture by instant tourist offers are also some of its side effects. That Žumberak is not immune to these phenomena is evidenced by sites such as the Gabrovo “Eco Park Divlje vode”, which is basically a large concrete pond with a questionable impact on the cleanliness of the Bregana River and with entertainment elements reminiscent of a miniature Disneyland.

II.3.c) Proximity to a large city as a migration attractor

A factor in the depopulation of Žumberak is, ironically, its proximity to the modern large city of Zagreb. Although this fact could be seen today solely as an advantage, the contrast in living standards and economic prospects between Žumberak and the rest of the country.

The urban environment, with the aforementioned traffic isolation, proved to be too large. Zagreb and the smaller urban centers in its surroundings demonstrated an economic attractive force that local prospects could not compete with.

II.3.d) Increase in real estate prices due to the purchase of holiday homes

One of the visions of Žumberak's future is that the process of emigration and dying out of the local population continues, with real estate and land being bought up by city dwellers for the purpose of holiday estates. The motivations for owning such a peaceful retreat in the countryside are fundamentally positive. The problem is that, if not controlled and countered by local perspectives for the indigenous population, this trend tends to crowd out authentic rural life – the prices that city dwellers are willing to pay for rural real estate are rising to a level completely unacceptable to the local population and becoming another incentive to sell their own land and emigrate. The result of this process is beautiful but dead villages that stand like backdrops of a former life and await their occasional visitors.

P.4. Opportunities

11.4. a) Demand for traditional cultural products and organic products

Most consumers will at least explicitly agree that we need healthy products obtained through sustainable production methods in our daily lives. Products of traditional culture also have their very real market niche, both due to their special qualities and for sentimental and cultural reasons. Organic and traditional production are categories that ideally overlap and rely on each other: traditional agriculture relied on plant and animal species that were suitable for cultivation in the immediate environment and on the raw materials that could be found there. This is precisely one of the basic ideas of most approaches to organic production, which are given additional market credibility by the stamp of tradition. On the other hand, a sustainable and ecological approach to the economy usually proves to be much more compatible with the local culture and way of life of a region than industrial farming.

11.4. b) Demand for rural tourism

Although most city dwellers are probably not ready to exchange their urban existence for a rural one, it seems that many of them still crave the occasional experience of “real” village life. Neighboring Slovenia has capitalized on its traditional culture and natural environment to the fullest: the highland villages offer affordable accommodation, excellent traditional food, and a wealth of cultural, recreational, and natural attractions.

II.4.C) Social need for natural recreational space

With today's physically inactive lifestyle typical of city dwellers, the additional need for movement and recreation is undeniable. For many, movement is natural

to the environment - hiking, cycling, sport climbing, etc., the most natural and complete form of recreation.

The infrastructure for these forms of recreation is also the infrastructure for developing rural tourism and marketing local products. After all, if you've already climbed Budinjak by bike, you probably didn't come there with the desire to eat a hamburger, but rather the traditional food and drink of this region will suit you better.

In general, in societies of healthy well-being and a culture of quality life, there is a noticeable trend of fully enjoying one's natural environment, which is increasingly noticeable in Croatia. The Žumberak region, with the sum of all the qualities already listed, is an excellent area for this type of activity.

II.4.d) Proximity to a large city as an economic and social driver and potential market

Technological progress, which has so far directed society towards increasing population, economic and cultural centralization, has recently become a valuable means of distributing information, creativity and social participation. With means of communication, such as the Internet, and the widespread use of personal vehicles, Žumberak is now, perhaps for the first time, in a position to benefit from the relative proximity of a large city.

Although it remains a fact that a large number of human activities are easier and more efficient to organize closer to major roads and population centers, today, through these new potential connections, Žumberak has the opportunity to become a space of significant social importance. The aforementioned ecological and traditional production and rural tourism play a major role in this, but the prospects for sustainable development are actually much broader than that. With minimal additional infrastructure investments, Žumberak can be an environment for many activities and ways of life that have so far been viewed as exclusively urban phenomena.

As many foreign, but also some Croatian, experiences show, with today's newfound connectivity, such rural areas can serve as a uniquely suitable and stimulating environment for the establishment of countless forms of creative small entrepreneurship, which will find their market both in the nearby large city and potentially throughout the world.

II.4.e) Possible influx of young and educated population seeking an alternative to urban living

Today, there is a whole subculture of young people who, for various reasons, are dissatisfied with urban existence and have aspirations towards life in the countryside. Ivan and Cvijeta are young, highly educated professionals who decided a few years ago to fulfill their aspirations of life in nature, creative peace and their own vegetable garden. Here is their story in Ivan's words:

"We were looking for a cheap facility in the countryside, and the advantage was given to mountainous areas... We were also attracted by the local variant of traditional wooden construction, with spacious rooms and a stone basement."

We considered the fact that it was declared a Nature Park to be a plus. In the end, we decided on 130 g. an old house in the farthest part of Zumberka, in the village of Ducici in the Radatovicka region.

… Zumberak seems like an ideal place to live. The advantages are very low living costs compared to city ones, low utilities, plenty of wood to cut down, which saves on heating, complete peace and quiet, an ideal recreational area, clean and high-quality land for farming, plenty of rainfall throughout the year, good mentality of the local population, low real estate prices…”

III. Strategy synthesis

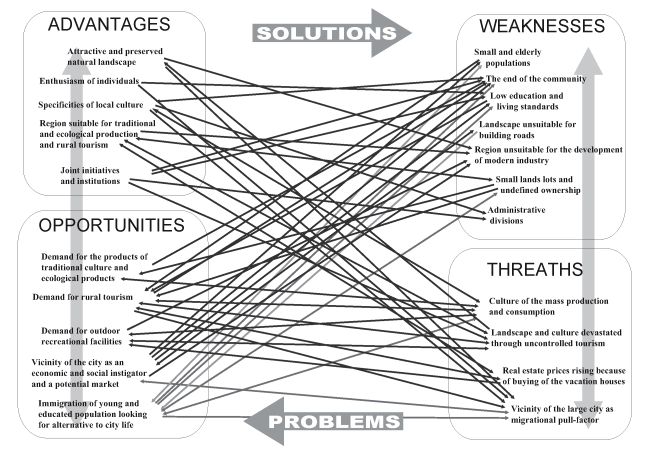

The results of the SWOT analysis give us in a very clear form a list of the problems we are trying to overcome and what resources we have at our disposal to reach their solutions. It is difficult to further formalize the ways of adopting a strategy for solving them. Given that the factors that appear in different situations are too diverse, this is the process that relies the most on creative thinking – it is necessary to create hypotheses from the given data and test them logically. However, there are methodological tools that facilitate this work. In classic business use, the results of the SWOT analysis are included in a matrix that establishes relationships between given problems and the resources we have at our disposal to solve them with possible actions. Given the complexity of the issue of the social development of an area and the large number of interconnections that occur in it, I devised my own method of visualizing the results that can be easily done with pen and paper and called it a SWOT-relational diagram.

Diagram 1. SWOT-relational diagram, phase 1.

In the first phase, we place the items included in the diagram in mutual relations depending on their influence on each other. Categories in the same column tend to be in a positive relationship with each other. Thus, an attractive and preserved natural landscape will have a positive impact on the influx of a young and educated urban population to Žumberak, while the collapse of the community will increase the influence of a large city as a migration attractor. Items in opposite columns show a negative relationship with each other, which can be mutual (specific local culture <=> collapse of the community) or unilateral (influx of a young and educated population <= relief makes transport connections difficult). When we fill the diagram with such relations, we will get an overview of the interrelationships of the resources we have and the problems we need to solve with them.

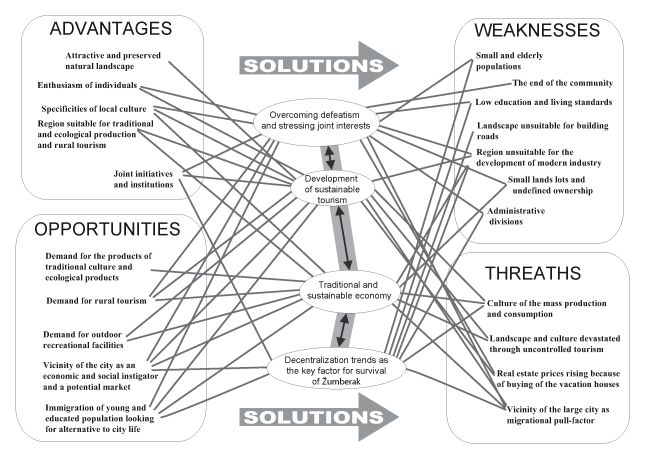

Diagram 2. SWOT-relational diagram, phase 2.

In the second phase, we need to rationalize the resulting interrelationships and use them to devise proactive approaches that will enhance the positive impact of the resources we have available on solving the problem, and neutralize their negative impact on our resources. When designing the required approaches, it is important to also aim for them to be in positive interaction with each other.

IV. Results

As one of the first items of any development strategy, it is important to determine its implementers. Without diminishing the role of other institutional actors (local authorities, counties, states, etc.), I see the coordinator of the implementation of the development framework obtained through this process in the “Žumberak and Samoborsko gorje Nature Park”. There are several reasons for this:

The Nature Park is given jurisdiction over almost the entire Žumberak area and the nearby Samobor Mountains – unlike local authorities and their three separate administrative units or the state and county, whose area of operation is much wider. It can use its conservation and expert authority to initiate and oversee joint initiatives between these levels and units of government.

The Nature Park already has a team of professionals qualified to care for the Žumberak environment, cultural heritage, and the development of local recreational and tourism potential. Further expansion of its mission to the area of preservation and revitalization of local culture and sustainable development requires only minimal reinforcement of this staff.

A nature park is an institution whose primary goal is the protection of natural heritage, but in areas where people have lived for centuries, natural and cultural heritage are not aspects that can be preserved separately. If a nature park accepts this integral conservation role, it cannot escape its developmental role: in order to truly preserve this cultural and natural heritage entity, it needs to be provided with a framework for sustainable development.

IV. 1. Overcoming defeatism and raising awareness of common interests

Given the widespread defeatism mentioned above, how can we encourage the remaining local population to take joint action to save their region and culture? To answer this question, we must understand that this feeling of defeat is not something that the people of Žumberak are themselves to blame for, but rather is imposed by changes in broader social circumstances and a lack of understanding and support from economic and political power structures. The people of Žumberak generally harbor very nostalgic feelings about their region and culture, but circumstances have convinced them that there is nothing left to save. The key to the solution lies in the words of Zvonko Šiljko, the newly elected mayor of the Žumberak municipality: “For fifty years, everything has been promised and promised, and nothing has been done. […] we need to go and talk to people in person, ask them where the problems are, how we can solve it together [..No one here in Zumberak has done that before.”

And indeed, from my conversations with the people of Žumberak, it seems to me that it doesn't take much effort to awaken their enthusiasm - if you present them with arguments that their area has something to offer the world and suggest some possible forms of cooperation in which they could participate, they will usually, with a dose of skepticism and caution, be interested in such proposals.

There are also enthusiasts among the local population. The will of these people should be adequately utilized – they can do a lot to gain the trust and cooperation of the rest of the community. With their help, a network of engaged local residents could be organized that would cooperate equally with the Park on development and conservation initiatives. This would not only provide us with valuable collaborators and a basic instrument for the restoration of Žumberak, but we would also probably make a major step in restoring the sense of meaning, uniqueness and emancipation of the local community, which would once again have the opportunity to participate in shaping its own destiny.

IV. 2. Development of sustainable tourism

The Nature Park has already done a lot in creating recreational and tourist infrastructure, and the local population recognizes this fact as a positive step forward. However, work needs to be done to create an approach to tourism development that would be coordinated with the local population so that they can reap the maximum benefits from it. As a modest start, the idea of organizing fairs and recreational events such as bicycle rides and hiking trips, which the local population could use to sell their own food and other products and promote their village as a tourist destination, is emerging.

It is necessary to work out a coordinated marketing approach for Žum-berk with the local population, to determine what kind of identity and which tourist products they want to present to the world, and to support them in spreading this message – both through the Nature Park institution and its communication materials, and through the media. For example, one could list households interested in hosting tourists and jointly determine some basic determinants of such an activity and their target audience. Once the appropriate preparations have been made, the Nature Park can serve as a link between these people and their audience, promoting their activities through its own website and other communication materials, and mediating their contacts with other media.

I would certainly include raising the hospitality culture of the population as part of appropriate preparations. The need to raise hygiene and accommodation standards has been mentioned. However, the issue of hospitality culture certainly does not stop at hygiene. Local residents need to be encouraged to become the main interpreters of their culture and landscape for their guests. Of course, it is necessary to offer them correct and complete information that was not previously available to them, for example, about the prehistoric history of their region, ecological values and problems, etc. However, let's leave it to them to interpret it and weave it into their personal story and direct life experience - this type of narrative is the most interesting and authentic for visitors.

Tourism needs to be linked to sustainable forms of local economy, both for the promotion of its products and for the creation of a complete tourist product. Households that would be engaged in catering should be linked to local producers as much as possible in terms of purchasing raw materials and household inventory. As has been mentioned many times, people will probably come to Žumberak to whiten local cheese and vegetables, and not those bought in a large shopping center. If it is also served in a local pottery or wooden bowl, the atmosphere will be complete, and the local economy and culture will be somewhat richer.

IV. 3. Traditional and sustainable economy

The development of tourism should also be used to raise awareness among the population about market opportunities arising from their traditional culture and landscape, which go beyond the tourist offer itself. If local residents could recognize a market demand for their products through tourism, it would be the best incentive for starting small businesses that Žumberak could receive.

The Nature Park could organize valuable support and professional assistance to the residents in this regard in finding sustainable and modern market-appropriate ideas and products, creating a kind of referral center for sustainable development. I believe that it is very important here not to repeat the mistakes of the past - the authorities have traditionally imposed new economic practices on the villagers by decree, explaining that what they have been doing so far is stupid and backward, and such an attitude only deepens the spirit of defeatism and passivity. Therefore, new ideas should not be presented to the population in the form of lectures that are tedious, incomprehensible and patronizing to them, but in the spirit of interactive communication - starting from the premise that while experts have expertise, local residents have lived here for centuries and know their region and their culture most intimately.

A series of meetings could be organized with interested local residents where they could discuss with experts and practitioners in the field the creation of conditions for the initiation of organic farming, with an emphasis on adapting these methods to their climate and their own agricultural heritage. Instead of imposing a uniform recipe on them in which they must blindly follow the instructions of experts, people should be encouraged to recognize and use in their own heritage those good and sensible ideas that have emerged during centuries of experience of living in this area, and combine them with sustainable aspects of modern agricultural progress.

Crafts and handicrafts could be helped to become more than souvenir production by giving people who practice them ideas on how to adapt their traditional products to the needs of modern life. If they are executed with good taste and respect for the original forms and materials, such innovations still retain the characteristics of the local culture, and in a way unfreeze it, open its developmental continuity and usher in the modern era.

It would be useful to work with the population on the restoration of the system of local exchange and procurement of raw materials. In this way, local primary, secondary and tertiary activities would be connected, the fragmented economy of this region would be restored, and people would meet as many of their needs as possible in their own community and for mutual benefit. In the world there are many successful examples of the creation of so-called of "local currencies" that are used to raise the local economy to a higher level that direct exchange cannot cover. Behind this concept stands a very serious economic theory,6 and many success stories worth studying.7

It would be worth considering the creation of a controlled Žumberak “brand” at the Nature Park level. Such a brand should embody the identity and qualities by which Žumberak presents itself to the world: as a place of pure nature, authentic tradition, hospitable people, healthy food, etc. As such, it would be a means of controlling and encouraging the quality of local products and services, and a valuable means of their promotion. While it is important to ensure impartiality and professional criteria, it is essential to involve the local community in the creation and awarding of such a brand: it is the real bearer and owner of the identity that is expressed through the brand. The brand should not be reserved only for products

6 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Local_currency

7 http://edupoint.carnet.hr/ond/ond.html

Žumberak tradition, but also to use it as a means of encouraging sustainable innovations that are in line with the identity it expresses.

IV.4 Decentralization trends as the key to the survival of Žumberak

If we want a truly sustainable future for this region, it is necessary to ensure infrastructure that will meet all needs and open up all perspectives of modern living. Among the basic needs that need to be met, the possibility of normal education, energy and water supply infrastructure, adequate transport connections and modern telecommunications facilities are essential.

Here we come to another dead end in Žumberak. As a prerequisite for real development and population renewal in Žumberak, it is necessary to satisfy all these needs, but why would the state reopen schools for which there are no students and build roads for such a small number of users? Why would commercial telecommunications companies bring modern mass infrastructure to Žumberak where they cannot possibly make a profit from it? The moral answer to this question is simple: because every citizen of this country and every region of it has the right to equal participation in the achievements of modern life and equal opportunities for development. However, based on the moral foundation of such demands, it will be difficult to expect their fulfillment in the foreseeable future.

Although it may not seem to have much contact with today's Žumberak reality, the internet is unusually important for the future of Žumberak. It is true that it is unlikely that we will persuade older farmers to use it, but the internet is a key prerequisite for the younger population to stay and come. In addition to opening an interactive channel of communication with the whole world that allows for the local performance of numerous jobs that previously required traveling to the city, the internet has enormous educational potential in both the formal and informal sense. In the informal sense, it is a source of an infinite amount of information, expanding human horizons and interests. In the formal sense, many countries that, for geographical and demographic reasons, need distance education have found the internet to be the ideal medium for this purpose. The internet is not a complete substitute for direct pedagogical contact, but the fate of children who have to travel sixty kilometers every day for school would be significantly eased by a tool that would allow them to do so only twice a week. There are already examples of such a practice within Croatia, and CARNET's EduPoint education center8 is actively working to expand the use of this technology.

But while it is unlikely that much can be done outside the usual slow and inefficient political channels in terms of paving roads and digging water pipes, as far as modern telecommunications and the Internet are concerned, technologies exist today9 which allow some of these problems to be addressed at the level of the Nature Park and the local community with the help of relatively small funds and a little expertise. If

8 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WiFi

If we are to truly consider the future of this region, we must be aware that no one will return to it or remain there to lead a medieval life based on subsistence agriculture – the internet is a key infrastructural prerequisite for modern existence.

IV. Conclusion

If the potentials presented in this study were realized, Žumberak could in many ways return this “investment” to society many times over. Such sustainable development of Žumberak would be a kind of precedent for the sustainable development of many other parts of Croatia. Given that most of our territory consists of rural areas, all of which are to a greater or lesser extent threatened by the sudden changes that surround us, the successful development of Žumberak would create a positive example of how to restore the lost meaning of rural life, give it economic momentum and a chance to contribute to the well-being of the wider society. But, perhaps most importantly, by putting Žumberak back on its feet, society would gain a unique space for a healthy, creative and fulfilling life for its members.

Our science should recognize part of its social mission in such development projects, encourage their implementation, and find "building material" for them in local culture and heritage. A prerequisite for this is the further development of methods by which we can translate the knowledge gained from ethnological research into development strategies.

Literature

Central Bureau of Statistics, Census of Population, Households and Dwellings, 31 March 2001,

http://www.dzs.hr/Hrv/censuses/Census2001/census.htm, (25.11.2008)

EU – Why do Geographical Indications matter to us?, http://jpn.cec.eu.int/home/news_ en_newsobj553.php , (25.11.2008)

Internet Center For Management and Business Administration Inc., SWOT Analysis http://www.quickmba.com/strategy/swot/ (25.11.2008)

Magdalenić, I., Župančić, M. (1996) Social and economic characteristics of peasant farms and Žumberak agriculture, in: I. Magdalenić, M. Vranešić, M. Župančić (eds.),

Žumberak: heritage and challenges of the future, (pp. 235-285). Zagreb, Committee for the celebration of the 700th anniversary of the name Žumberak

Magdalenić, I., Stambuk, M., Vranešić, M., Župančić, M. (1996) Conclusions and recommendations, in: I. Magdalenić, M. Vranešić, M. Župančić (eds.), Žumberak – heritage and challenges of the future, (pp. 315-318), Zagreb: Committee for the celebration of the 700th anniversary of the name Žumberak

Muraj, A. (1989) I live means I live: an ethnological study on the culture of housing in Sošice, Zumberac, HED

Swan, R.; Witt, S. Local Currencies: Catalysts for Sustainable Regional Economies, http://www.smallisbeautiful.org/publications/essay_currency.html (25.11.2008)

Sola, T. (2001) Marketing in museums: or about virtue and how to make it known, Croatian Museum Society

Stambuk, M. (1996) Introduction. in: I. Magdalenić, M. Vranešić, M. Župančić (eds.), Zumberak – heritage and challenges of the future, (pp. 315-318), Zagreb: Committee for the celebration of the 700th anniversary of the name Zumberak

Responses